Cette publication est également disponible en :

![]() Français

Français

During a perfume’s life cycle, the formula may change. For what reasons? In what way? With which constraints? Alexandra Kosinski, senior perfumer and Director of Perfumery UK for British fragrance house CPL Aromas, explains how perfumers go about it.

How does reformulation come into play?

Usually it happens due to stricter regulations concerning the use of a raw material. The composition company, which owns the formulas, lists the perfumes that contain the ingredient in question and warns the brands that use it of the need to reformulate. The price the brands pay to purchase the concentrate must remain the same, so the changes mustn’t have an impact on cost, which isn’t easy. If we take the example of Lilial [the world’s best-selling lily-of-the-valley-scented molecule, affected by a recommendation to limit its use by the IFRA since 2015], its substitutes may cost twice as much.

Who is tasked with revisiting the formula?

If possible, the creator of the fragrance will do it: it’s an industry rule, because of concerns over confidentiality and the fact that no one knows the formula better than the creator. In bigger structures, a specific team is charged with the task. It usually includes junior perfumers, since reformulating is an opportunity to learn. And it can be interesting to work in a team. As for myself, I enjoy the exercise; I see it as a game, a puzzle.

How do you go about it?

We start from the latest version released for sale, since its formula is up to date and contains fewer ingredients that need changing – with the risk of diverging further and further from the original version. We begin by trying to replace the problematic element with another ingredient. If we take the case of Lilial, we can try to replace it with Florosa or Bourgeanol, which have similar olfactory profiles. Except that every raw material has its own specific evaporation time, so it’s impossible to find an ingredient with exactly the same qualities. The degree of difficulty also depends on the perfume’s olfactory family. For example, if it’s mostly made up of floral notes, we can use more of them in the formula in order to replace Lilial. But if the Lilial is mixed in with woody notes, its absence will be much more obvious. In this case, we usually have to overhaul the entire formula in order to restore the balance. In a situation where we have to remove a natural ingredient, we can make a list of the molecules that it’s composed of and recreate its scent while excluding the ones that pose a problem. All these adjustments may take anywhere between one month to two years.

Why do reformulations remain a taboo subject for brands?

In the 1980s, the disappearance of animalic notes in particular led to major reformulations that significantly modified fragrances’ olfactory profiles. The brands didn’t talk about it, but consumers noticed the changes and lost confidence. It’s always a delicate topic of discussion. But these days reformulations are far closer to their predecessors. Perfumers are seeing their palettes steadily expand and supplies are more secure. For example, when a patchouli harvest burned down, you had to go without it for a year, which had obvious impacts. Nowadays this doesn’t happen as frequently.

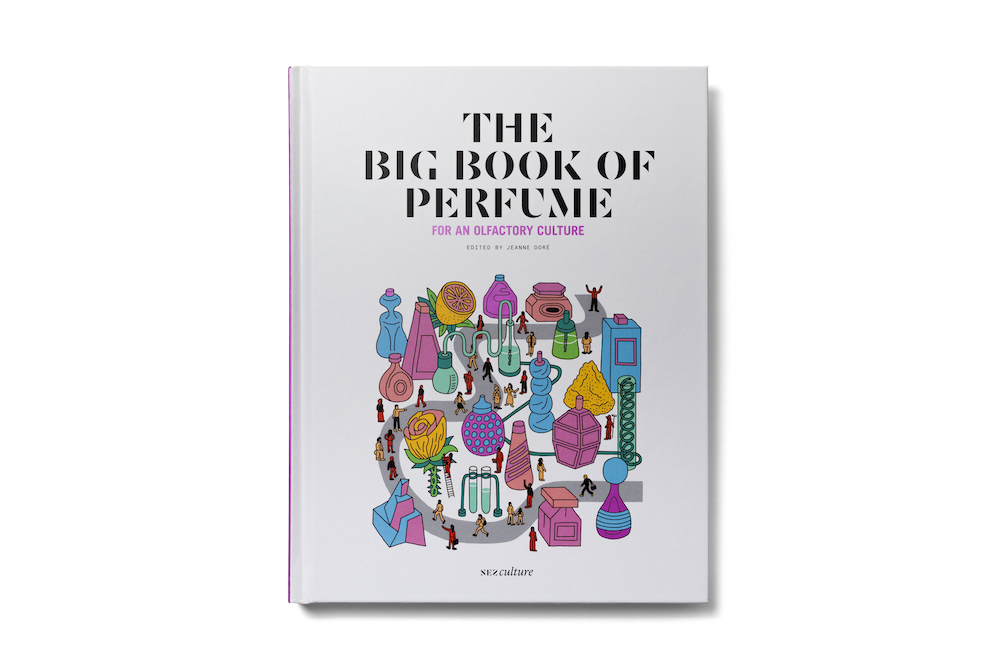

This interview is from : The Big Book of Perfume, Collective, Nez éditions, 2020, 40€/$45

- Available for France and international: Shop Nez

- Available for North America: www.nez-editions.us

Comments